In biblical mythology and Jewish folklore, the Golem is a creature typically made from inanimate matter, often clay or mud, brought to life through mystical means. The Golem is associated with ancient Jewish mysticism, particularly within the traditions of Kabbalah. Though not mentioned directly in the Hebrew Bible, the concept of a Golem has roots in biblical creation themes and has evolved through centuries of Jewish storytelling, becoming a powerful symbol of protection, creativity, and sometimes unintended destruction.

Origins and Creation

The Golem concept stems from the idea of humans being formed from dust or clay, as found in the creation of Adam in the Book of Genesis:

“Then the LORD God formed a man from the dust of the ground…” (Genesis 2:7)

In Jewish mysticism, this biblical creation process is seen as a template for the creation of a Golem. However, while God breathes life into Adam, giving him a soul and full consciousness, a Golem is typically animated through divine names or sacred words, inscribed on its body or placed in its mouth. It lacks a soul and, as such, is more of a vessel or automaton, not a fully sentient being.

The creation of a Golem was usually attributed to rabbis, scholars, or mystics deeply versed in Kabbalistic practices. They would inscribe the word “Emet” (אמת), meaning “truth” in Hebrew, on the Golem’s forehead or write it on a piece of parchment placed inside its mouth to animate it. To deactivate the Golem, the first letter, “Aleph,” would be removed, changing the word to “Met” (מת), meaning “dead.” This wordplay reflects the tension between life and lifelessness that characterizes the Golem.

The Golem as Protector

One of the most famous legends involving a Golem is that of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague, a 16th-century Jewish mystic. According to the tale, Rabbi Loew created a Golem from clay taken from the banks of the Vltava River to protect the Jewish community from anti-Semitic attacks, particularly blood libel accusations. The Golem would patrol the streets and protect the Jews from harm, performing tasks or standing guard. The story of the Golem of Prague is among the most well-known variations of the Golem myth and serves as an enduring symbol of Jewish resilience and defense against persecution.

The Role of the Golem in Jewish Mysticism

The creation of a Golem is linked to the mystical traditions of Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Creation), an ancient text that describes the creation of the universe through the manipulation of the Hebrew alphabet and divine names. By understanding the sacred letters and their corresponding spiritual energies, a learned rabbi or mystic could theoretically create life, albeit an imperfect one, through a Golem.

In Kabbalistic thought, the Golem represents the human desire to imitate God’s creative powers, albeit in a limited and often flawed way. The Golem serves as an embodiment of human potential for creation, yet it also warns of the dangers of overreaching—creating something that lacks the spark of divine spirit, resulting in an entity that can be both helpful and dangerous.

The Duality of the Golem: Helper and Destroyer

While the Golem was typically created to serve or protect, many stories explore the darker side of this creature. Because it lacks a soul, the Golem can become uncontrollable or violent, turning on its creator or causing unintended destruction. In the Golem of Prague legend, for instance, Rabbi Loew deactivates the Golem after it becomes too powerful, losing control of its actions. In some versions of the story, the Golem runs amok, threatening the very people it was created to protect.

This aspect of the Golem as a potentially destructive force is often interpreted as a warning about the dangers of seeking too much power or control over life and creation. It highlights the ethical questions surrounding the limits of human intervention in divine processes and the consequences of manipulating forces beyond full human comprehension.

Symbolism of the Golem

The Golem has come to symbolize several important concepts within Jewish tradition and beyond:

- Creation and the Divine: The Golem represents human attempts to mirror God’s creative powers, reflecting a deep theological question about the nature of life, creation, and the divine spark. It also explores the boundary between life and lifelessness, being a created being that can function but lacks a soul.

- Protection and Defense: As seen in the Golem of Prague story, the Golem stands as a powerful symbol of protection for the Jewish community in times of threat. The Golem’s role as a protector resonates with the historical struggles of the Jewish people, who have often faced persecution and sought both divine and mystical forms of defense.

- Uncontrolled Power: The Golem also serves as a metaphor for the dangers of unchecked power or creation without responsibility. The fact that the Golem can become uncontrollable reminds us of the limits of human understanding and the potential consequences of wielding power without foresight.

- Ethical Boundaries: The Golem legend addresses the ethical and spiritual boundaries of creation. It reflects concerns about the proper role of humans in relation to divine authority, as well as the consequences of crossing those boundaries by playing a creative role traditionally reserved for God.

Modern Interpretations

In modern times, the Golem has become a symbol used in literature, art, and popular culture, especially within discussions of artificial life and technology. The Golem legend has inspired numerous works, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to modern science fiction involving robots, artificial intelligence, and bioengineering. The ethical questions raised by the Golem about creation, control, and responsibility remain highly relevant in the context of technological advancement and the potential consequences of artificial life forms.

In sum, the Golem is a powerful figure in biblical mythology and Jewish folklore, embodying the complex relationship between creation, power, and morality. As both a protector and a potential destroyer, the Golem’s legacy continues to inspire reflection on the limits of human creativity and the responsibilities that come with wielding great power.

Description

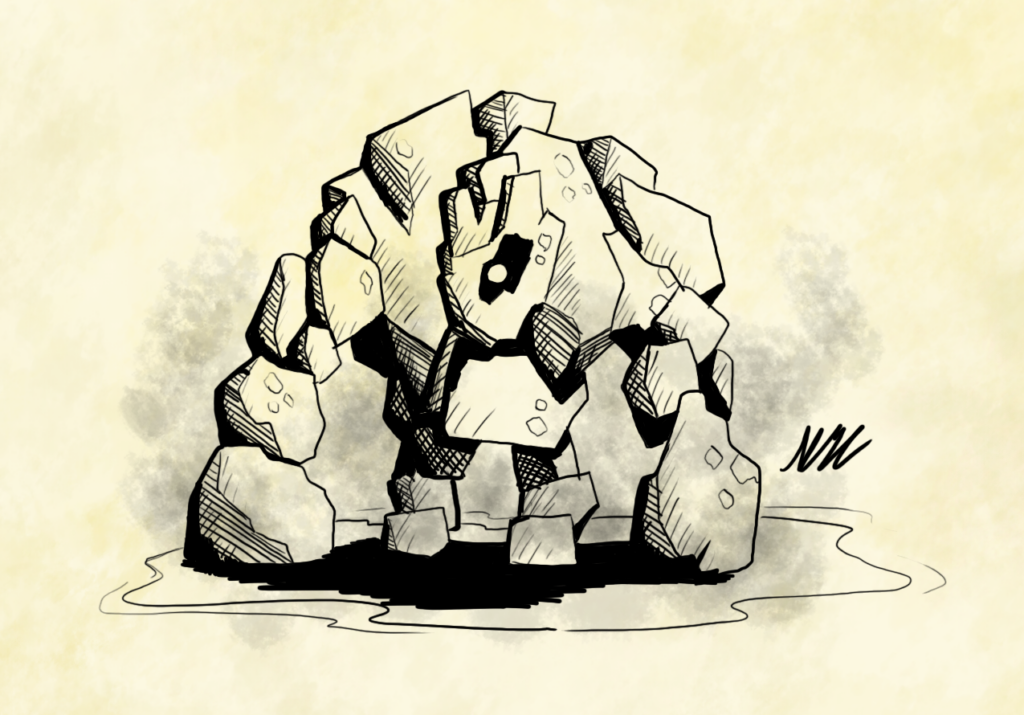

A golem is an animated being created from any inanimate matter in Jewish folklore [1]. Usually, it is clay or mud but in recent media stone, iron, gold, and other materials have also become very common.

The word golem was used in psalms and medieval writing to mean an amorphous, unformed material [1].

The oldest golem story dates back to early Judaism. In the Talmud, Adam was initially created as a golem as his dust or mud was formed into a shapeless husk [2].

Originally the main disadvantage of golems was their inability to speak [3].

Golem stories have been popular in many different countries in the world including Israel, Germany, the Czech Republic, and Prague.

Golems Moral Connection

In many stories, the golem is connected to hubris as the creator makes the golem help with tasks or perform a specific task. Later on in the story, the creator of the golem has to pay due to the golem always taking the task given to them literally (The golem cannot understand similes, metaphors, and sarcasm) [4].

In the earliest modern form of the golem story, the Golem of Chelm grows to be enormous and uncooperative. In some versions of the story the rabbi who created the golem needs to destroy it by resorting to trickery [1]. In some versions, this leads to the golem breaking and crushing the rabbi [5].

In Yiddish and Slavic folklore there is a similar story of a couple making a clay boy and leaving him by the fire to dry while they go out. When they return the boy has come to life which makes them very happy. The boy never stops growing however and eats more and more devouring their food, their livestock and finally them [6].

Norse Myth,

In Norse mythology, there is a similar creature to a golem. Mökkurlálfi or “mist-calf” is described as a mighty creature made of clay [7].

Sources:

[1]: Idel, Moshe (1990). Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN0-7914-0160-X. page 296

[4]: Introduction to “The Golem Returns”Archived 12 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 September 2011.

[5]: Kieval, Hillel J. Languages of Community: The Jewish Experience in the Czech. Lands. University of California Press; 1 edition, 2000 (ISBN0-5202-1410-2)

[6]: Cronan, Mary W. (1917). “Lutoschenka”. The Story Teller’s Magazine. Vol. 5, no. 1. pp. 7–9.

[7]: Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-983969-8.

Author

Josh Morley holds a Bachelor’s degree in Theology from the Trinity School of Theology and a Diploma in Theology from the Bible College of Wales. His academic journey involved interfaith community projects and supporting international students, experiences that shaped his leadership and reflective skills. Now based in Liverpool, Josh is also the founder of Marketing the Change, a digital agency specializing in web design and marketing.

View all posts